THE NEST INVESTIGATES: Online Learning with the VSB’s Vancouver Learning Network

UPDATED DEC 18, 2021 FOR CLARITY

UPDATED JAN 15, 2022 WITH RECENT FOI RESULTS & COMPLETION RATES

After reviewing dozens of documents, 85 written testimonies, social media posts, board meetings, student interviews, and data obtained through freedom of information, a months-long Nest investigation of the Vancouver Learning Network reveals a set of mixed student experiences that make for an educational journey of either smooth sailing or academic shipwreck — with little in between.

As thousands of secondary students turned to VLN throughout the pandemic, most who took a course other than Career Life Education 10, a graduation-required course popular to defer online, say the program misses the mark.

The majority of students enrolled in Math, Mandarin, French, Chemistry, English, and Life Sciences voiced disappointment.

Students agree that the district needs VLN, and said they are reliant on it to fulfill their education path. But for the non-CLE crowd, it isn’t currently meeting their needs.

A BRIEF OVERVIEW

Founded in 1990, the Vancouver Learning Network is the VSB’s dedicated online school, offering Ministry-approved K-12 courses taught by district teachers. VLN’s website says that they offer over 90 courses and fulfill a wide variety of education needs as an alternative to traditional in-person learning.

The Nest reviewed VLN’s five-year enrollment and budget data, obtained through a freedom of information (“FOI”) request filed on August 27. From the 2016/2017 school year to 2019/2020, enrollment hovered between 4400 and 4700 before soaring to nearly 7400 in 2020/2021.

The bulk of enrolment is concentrated in the upper secondary grades, with 7 in 8 VLN students in grades 10-12.

Budgetary information shows a similar trend, with total revenues between $4.8 and $5.1 million per year from 2016/2017 onward before climbing to $9.3 million in 2020/2021. That year was largely supported by a $7.7 million operating grant, an increase of 83 per cent from the previous year, as well as an additional $950,000 Safe Return to Class Grant from the federal government.

Total expenditures amounted to $5.4 million, leaving net revenue at $3.9 million.

The Nest requested multiple other records, including third-party contracts, through freedom of information requests. However, they were inaccessible, as the VSB charged a fee of $220, later reduced to $100, for processing. The VSB refused to fully waive the fee under both public interest and affordability exemptions, citing a lack of evidence that The Nest would be unable to afford it, and that the records requested were not in the public interest.

Multiple follow-up FOIs were filed and are still pending as of publication date.

A 2020 statement from Canadian education technology company D2L, provider of the popular Brightspace learning platform, announced that VLN had selected them to “deliver online summer school courses to more than 3000 students” after the VSB chose to take the seasonal program virtual. D2L’s contract was one of the third-party contracts requested through freedom of information that was inaccessible due to the fee.

While the VSB did not answer any questions on how the pandemic challenged the program, as with nearly every educational institution, COVID-19 likely presented VLN educators with an unprecedented mandate.

THE ONLINE LEARNING MODEL

Like most online schools throughout the province, VLN uses a distributed learning model for its courses.

The distributed learning model is a technology-based, non-consolidated, and student-led method of teaching. Course material and any required resources are available online, usually on a centralized website.

This format can have many benefits, including flexibility and convenience for students, along with self-directed and self-paced lessons.

However, experts agree that distributed learning models have many flaws.

A 2017 paper analyzing distributed learning coordinated by Stephen Downes, an online learning expert and member of the National Research Council of Canada, said the agency given to students in this model was also one of the major reasons students failed to complete their courses.

The lack of a rigid structure and explicit directions from teachers might work for university-aged students, but may fail to take hold in a high school environment, where students do not have the same sense of independence and reliability.

Without the face to face interaction with peers and instructors, students have a much harder time understanding concepts and ideas, considering the lack of instant feedback from teachers, which can convey the nuances and complexities of certain topics.

The face-to-face aspect of engaging students in a classroom is seen by many educators as an important element of teaching and learning.

WHAT STUDENTS SAID

The Nest collected 85 written testimonies from VLN students. Many outlined that they took a VLN course to add flexibility to their in-person schedules. Some chose VLN to pursue personal interests.

The Nest is not disclosing their identities for the avoidance of source retribution.

Primarily for students who had taken CLE 10, VLN’s platform worked well. Many wrote about their ease in the course, with one student sharing “I liked how the assignments were very organized and the instructions were easy to follow.”

But for those enrolled in other courses, the majority voiced the opposite.

The discrepancy that was found within satisfaction rates is cause for concern. Students said certain courses had clear, well-presented content; while others had a confusing format and content that was difficult to comprehend.

Students complained that the number of errors in VLN’s content made it challenging to follow. While several commented on the frequent use of incorrect spelling and grammar, others pointed out faults in the material itself. One student grew frustrated over a math problem, stating “the question could not be answered as there were no sufficient variables.”

Multiple students confirmed that they had taken quizzes and tests that contained unsolvable questions or technical errors that impacted their grades.

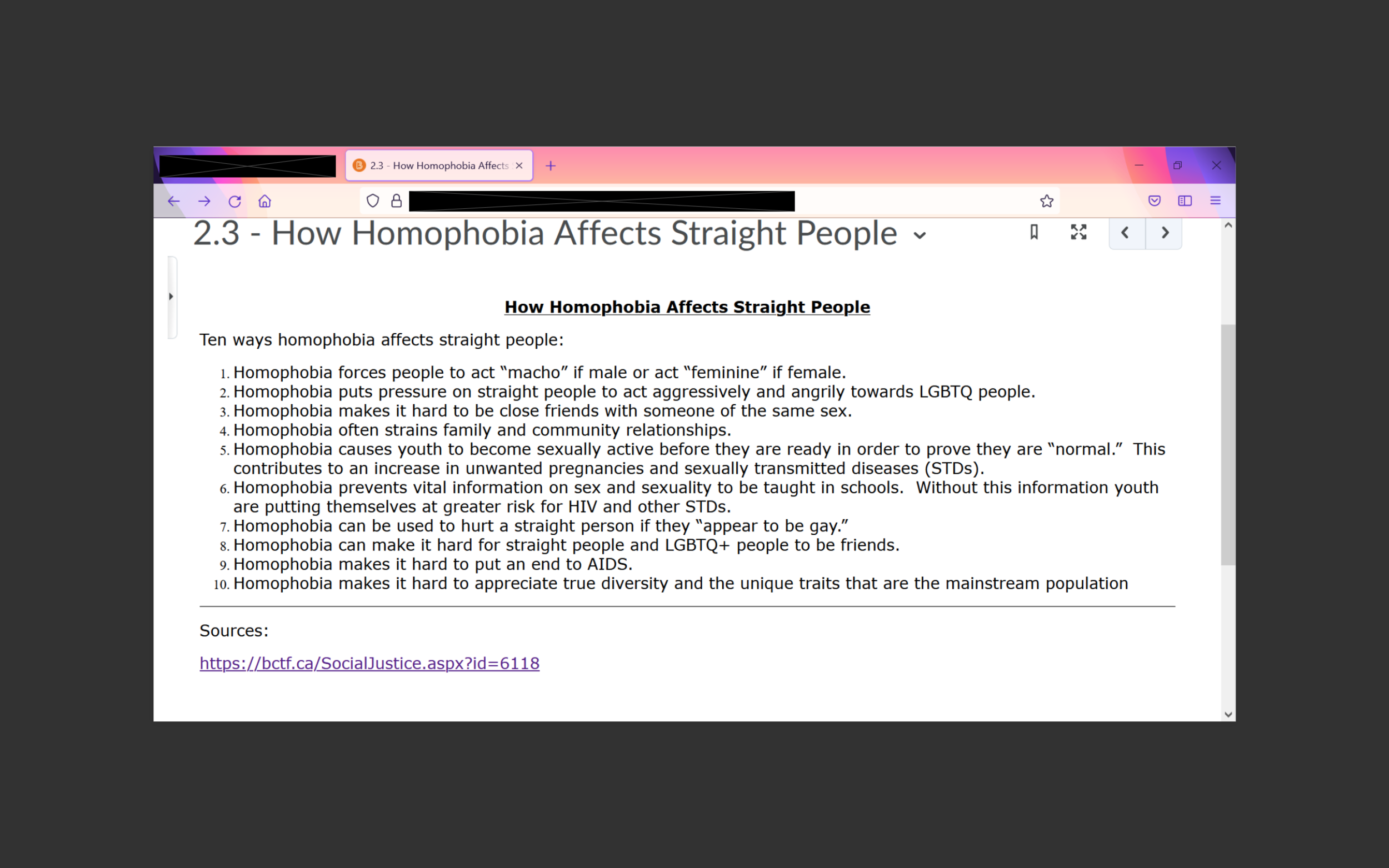

One specific issue raised with content were inaccuracies and insensitivities in material related to the LGBTQ+ community in VLN’s Social Justice 12 course. A student currently enrolled sent The Nest screenshots of Lesson 2.3, titled “How Homophobia Affects Straight People,” followed by a list of 10 reasons. The student shared they are “considering dropping [Social Justice 12]” because they “found the content to be homophobic.”

Screenshot provided by VLN student. Redactions made to protect their identity.

The Nest showed Lesson 2.3 to Hamber’s Gender-Sexuality Alliance (“GSA”), which said the lesson as presented could mislead students’ understanding of homophobia’s pervasiveness, as well as their understanding of gender and sexuality.

According to the Ministry of Education’s standards for online learning, “the learning object [must be] socially, culturally, and age-appropriate for the intended audience.”

Assignments like this could point to a lack of review and quality control in course material.

Additionally, lessons rarely sufficiently prepare students for their midterm or final exams, which often comprise over half of their final grades. “The final exam was extremely difficult and I felt as if I hadn’t learned most of what was on the test,” said one student. Another voiced that “the content doesn’t always coincide with the work and tests.” Many students echoed these sentiments.

The most common issue was that teachers were difficult to contact. One student said that while they “[learned a lot] about First Nations Peoples, the lack of support and guidance, along with what felt like never-ending content, drove [them] into a bad mental state. Another student said that their VLN teachers “were unresponsive with emails,” which “affected [their] mental health a lot.”

This may be due to large class sizes in certain courses, as one student points out that “the teachers had so many kids to deal with.”

Though not all students felt this way. “For almost every assignment I emailed my teacher for clarification, and he got back to me quite quickly. When I handed in my assignments, he also graded them extremely fast, something I have not experienced with teachers at school,” a student taking Media Design 11 explained.

In general, the vast majority experienced difficulty in communication with teachers.

At times when VLN teachers were present, some students claimed that they were uncooperative. “My teacher made a mistake marking my test. While that in itself would be fine, he refused to correct it, arguing with me for several minutes,” one student, who eventually met their teacher in-person, explained, “I…[told] him I would see the principal and a couple of minutes later the teacher sent me an email saying he would correct his work.” The student was enrolled in Chemistry 11.

Another student complained that their English 12 teacher had “unfair marking” for which they “did not provide proper feedback or reasoning.” Those who found themselves in similar situations felt discouraged when their teachers took “days or weeks to respond” or simply ignored their requests for clarification.

Most students – including those who said they typically thrive academically – admitted that it was challenging to succeed in VLN’s learning environment. One confessed, “The VLN gave me little to no support throughout my time there. I am usually a successful student and I truly struggled. I felt as though they did not care [about] student success and I frequently felt discouraged…I did not leave my courses feeling educated or empowered.” They took French 10 and Comparative Cultures 12.

In a virtual setting, many issues, such as unfair marking and content errors, that occur in traditional schools are made significantly worse by a lack of consistent access to a professional educator.

Students overwhelmingly said the level of student-teacher communication was largely inadequate, and ultimately impacted their learning. But that isn’t exactly news to the VSB, or VLN.

CLEAR COMMITMENTS AND UNCLEAR RESULTS

Nearly six years ago, the VSB identified some of the same issues that VLN students are raising today.

Coming off the heels of years of sub-provincial average performance, district management was keen to improve success within the program.

A March 2016 report entitled “Proposed Changes to the Vancouver Learning Network” made specific comments about teacher-student communication, saying “it became apparent that centralized programs where teachers are at a distance and communication is minimal tend to yield lower completion rates than those that are embedded or blended into a neighbourhood secondary school.”

The report recommended that VLN “support a blended student-learning model where students have a greater opportunity to connect with teachers from a local neighbourhood school” and “increase the opportunity for face-to-face support.”

It went on to say that “improving communication and extending relationships between students, teachers and parents may also be an outcome [of a reorganized VLN model]. Overall we would expect to see increased student connectivity, the opportunity to integrate students back into a regular school environment, the ability to engage students in a variety of ways and overall, an increase in [online learning] completion rates, thus an increase in student success.”

The report made direct connections between the opportunity for face-to-face support, a form of increased communication, and student success. The school board approved its recommendations unanimously in April 2016.

Whether those recommendations went on to improve student-teacher communication compared to previous levels remains unclear.

The report concluded by mentioning “District staff are committed to bringing a report forward in June of 2017 which reviews the model, provides data on student success and other relevant information”, but no such report could be found. An FOI was filed in November to obtain a copy.

When the VSB returned our FOI in January 2022, we received a letter that simply said no records were found, writing, “due to unforeseen circumstances, the production of a report was never undertaken.”

The Nest reached out to the District Parents Advisory Council for what insight the body may have into the VLN student experience, and what issues they may have seen.

“We’ve heard from parents that the success rate is not as high as in-person schooling, but not only is [what we know] anecdotal, it lacks detail,” said DPAC Chair Gord Lau. “With many parents looking to VLN as an option, they’ve discovered that VLN requires a high level of self-direction from students. Many parents and students are looking for an option that includes more teacher guidance than VLN.”

The Nest sought VLN’s success, or completion, rates, but obtaining that information quickly became problematic.

COMPLETION RATES?

The Nest tried multiple times both through communications staff and FOI requests to access VLN course completion data, but despite finding partial statistics in various reports and documents, the VSB had inconsistent answers as to whether or not they held that information.

The same March 2016 report discussed “Historically, VLN completion rates fluctuate in the 50-60 percent range and are below the provincial average.”

With 2014/2015 data confounded by labour disputes between the BC Teachers Federation and the province, the most informative completion rates came from years 2010/2011, 2011/2012, and 2012/2013, at 56.9%, 59.3%, and 60.0% respectively, all falling 10-15 per cent below the matched provincial average. However, that data alone is too old to fully represent VLN of the present.

The report went on to make multiple other mentions of increasing completion rate as a target of the proposal, specifically saying in its aforementioned conclusion that it was “designed to enhance opportunities and increase course completion rates for students.”

It was made clear that completion data was relied upon as a key success indicator, so The Nest attempted to repeat the board’s method and match current VLN rates with provincial data.

Upon an FOI request for completion rates from 2010/2011 to present, which technically included years The Nest had already viewed in the 2016 report, the VSB said they didn’t have that data. An FOI analyst wrote that “course completion status is not available for discrete periods of time such as a school year or calendar year. The Vancouver School Board does not track course completion rates as a data set,” despite records of that exact nature known to exist within board documents.

Further research found a presentation delivered to the VSB Student Learning & Well-Being Committee in February 2021 revealing that “57% of students who started courses in [the] 2019/2020 school year have completed their courses,” adding that more completions were expected between then and June 2021. Upon review of footage from the corresponding board meeting, trustees and management spent little time discussing completions, with Associate Superintendent Jody Langlois saying that the continuous entry model makes completion a difficult dataset to track.

The February statistic, produced in response to questions in a November 2020 meeting, was the most recent available completion data, making it a year old, and insufficient, to use as VLN’s current course completion rate.

In an email, VSB Communications reiterated what the Associate Superintendent had said months earlier about the continuous learning model, and that they could not provide The Nest with such data.

After requesting all general “completion metrics” from the 2014/2015 school year onward through FOI, an analyst said that since the 2016 report, “the process in collecting those statistics [have] not been carried forward or maintained,” and that the rates were only collected for single-time use.

The Ministry of Education supplied The Nest with provincial completion rate data for online learning in response to a freedom of information request. Records show that the provincial average for combined public and independent schools’ online course completion rates for grades 10-12, VLN’s core demographic, was 68.86 per cent in 2019-2020.

In a September 2021 Notice of Meeting, the VSB acknowledged in reference to general learning measurement, “completion rate is the most widely referenced measure of system performance.”

From what The Nest has found, the school board does not have what their own management describes as an essential performance indicator, one they’ve historically used to evaluate VLN. Both FOI and communications staff said course completion isn’t tracked, but available documents suggest otherwise. The VSB had been tracking completions when management presented inconclusive data in February. Why that was never acknowledged by district staff is unknown.

So what is VLN’s completion rate? When this investigation was first published in December 2021, The Nest produced an estimate. We wrote “Based on information from past years, VSB and DPAC sources, board documents, and data from the Ministry, VLN’s current course completion rate is best described as low, meaning a number estimated between 55 and 70 per cent.”

Two of The Nest’s FOIs from November were still pending. On January 11, 2022, The Nest received the first conclusive completion data produced specifically in response to our request.

Of the 9002 courses started between January 1 and December 31 of 2020, only 5561 had been completed by the day our FOI was filed. The VLN’s completion rate, for courses started in 2020, is 62 per cent, as of November 25, 2021.

(Note to Readers: At several points during The Nest’s investigation, our emails and FOI requests were acted upon by VSB staff who were not the intended recipients. The VSB organized two agendaless meetings with the Nest, in one where the filing freedom of information requests was discouraged, and in a second, without The Nest’s prior knowledge or consent, VSB management invited their own suggested sources to answer questions sent to communications. The Nest quickly ended the second meeting before any conflicts of interest could impede independent reporting.)

REVIEWS ARE RELATIVE, BUT TELLING

Some students have taken to the open internet, specifically, Google Reviews, to voice their VLN struggles.

While famously amplifying both the good and bad, Google Reviews are relative. VLN’s further confirm the sense of disproportionate dissatisfaction compared to traditional schools students told The Nest in their testimonies.

The Nest gathered Google Reviews data for every VSB secondary school, with all schools presenting a score between 3.6 and 4.4, and district a mean of 3.91 and a median of 3.90 out of 5.

VLN comes in dead last at just 2.4, well below both group metrics.

Many negative 1 or 2 star reviews posted within the last year displayed high ‘thumbs-up’ reaction counts, with as many as 12 users liking a review that bluntly stated “Student needs are not met. Material is poorly presented online.”

On a platform like Google Reviews, where interaction from users is low, it is significant that 12 users reacted to such a message, suggesting that many more students feel the same way.

Other self-identified students wrote of the same issues found earlier: teacher-student communication delays, unfair assignments and assessments, technical errors in quizzes and resources, and large variances in study material versus tests. A sizable number of reviews go into lengthy, multi-paragraph detail that includes specific examples from the courses they were enrolled in.

Many users wrote their reason for enrollment was their parents’ decision to keep them online for the duration of the pandemic.

Even when accounting for the amplification factor on review platforms, VLN’s Google Reviews are telling. No other VSB secondary school had a score close to 2.4.

VLN staff appear to have previously monitored Google Reviews. Multiple replies using the sign-off “VLN” have been found in response to both positive and negative reviews, often asking for elaboration in effort to improve educational experience. It is unclear whether the VLN continues this practice.

CHANGES ARE COMING TO ONLINE LEARNING, BUT WE DON’T KNOW WHAT THEY MEAN FOR VLN

As part of a series of large province-wide changes to the online learning model, the online learning system will undergo changes in the 2022 and 2023 years. The new model, according to the government, emphasizes an increase in certified online learning schools and “a quality assurance process that will help online schools follow and share best practices.” The plan promises equal access, flexibility, quality of teaching, and support for educators.

Along with replacing all mentions of “distributed learning” to “online learning”, the changes state that students may only register for online learning programs in their district. To cross-register, they must attend a certified Provincial Online Learning School (POLS). As of now, it is unclear how many schools will be certified, which could severely limit access to specialized online learning programs by the students who need them most.

Multiple VLN students said that after their experience, they took their subsequent online learning needs to other programs within British Columbia, including Navigate Nides in Comox and EBUS Academy in Vanderhoof. All students who said they enrolled with these schools voiced their praise of the quality of instruction compared to VLN.

With the province’s plan still in its early stages, it remains to be seen whether the specifics of this plan will resolve the problems VLN students face.

LESSONS (RE)LEARNED

The last known comprehensive review of the Vancouver Learning Network occurred nearly six years ago, and the same issues identified then are still hindering online secondary education.

The pandemic has provided the VSB a valuable opportunity to reexamine the program’s efficacy and work towards improvements. With potentially thousands of students receiving an education that doesn’t meet their standards, it’s clear that VLN needs a quality boost.

As of publication, half of VLN secondary students who spoke to The Nest say they would not recommend the program to their peers.

Neither the VLN Principal nor Vice-Principal could be independently reached for comment. The Vancouver School Board declined to comment on the findings of the investigation.

The Griffins’ Nest Editorial Board would like to thank the civil liberties lawyers who helped ensure the publication of this investigation and thank the X-University (formerly Ryerson) Center for Free Expression, BC Civil Liberties Association, and BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association for their support of student journalism.