Students, Teachers Speak Out about ChatGPT

OpenAI CEO Sam ALtman | Photo Credit: JASON REDMOND/AFP via Getty Images via Business Insider

The Microsoft-backed company OpenAI has been a rising star in the artificial intelligence landscape, making headlines around the world with their service ChatGPT, a text-based interface where users can interact with a version of the GPT-3 language model developed by the company.

These large artificial intelligence systems are trained on a vast amount of text; GPT-3 was trained on 45 terabytes of data, including data from CommonCrawl (which searches and logs the web), books in the public domain, and Wikipedia. Based on this data, these systems learn to generate new text, such as short responses to questions, poems, essays, and short stories.

Language models such as GPT split a given text into tokens; the AI attempts to predict the next token, using the previous tokens as context. This method of training is known as “generative pre-training”, hence the name GPT, a “Generative Pre-trained Transformer”. Due to it being exposed to such a large corpus of text while pre-training, GPT is thus capable of attempting to complete tasks it was not exposed to while training.

However, AI models have also incited concerns on the validity of its information; ChatGPT often opts to provide incorrect assumptions instead of explaining its shortcomings. While the ChatGPT model does have safeguards against biased language, users have noticed that it may produce racist or homophobic text at times as reported by The New York Times, almost certainly a result of being trained on the Internet.

Because of its ability to generate coherent, convincingly human-like text responses to essentially any question, ChatGPT and other language models have wide applicability in schools. The use of GPT-based language models to complete schoolwork is a point of increased discussion amongst many educators, who have voiced concerns about students asking AI to do their work for them and passing it off as their own.

Despite ChatGPT’s growing popularity, not everyone at Hamber is using it. Many of the students and teachers The Nest interviewed use it rarely, if at all.

Daniel Brandão (11) notes that AI models can be helpful for programming. “Whenever I get an error or I need to make something that already exists, I use it to create said code, or fix said code, so that I don’t have to do it by myself,” he said. An anonymous student (12) disclosed that they use it for “documents that involve English topics, or about anything with English in it.

Neither Mr. D. Mugford (English) nor Mr. N. Norcross (English and Social Studies) have used ChatGPT or other text generative AI. “I first only really heard about it coming out maybe six months ago,” Mr. Mugford told The Nest, revealing that he “was quite alarmed by it.”

Mr. R. Arkiletian (Computer Science) recalled asking ChatGPT to write some code for him. “It’s still in its infancy, but [...] I have no words to describe it. I was quite impressed by it.” He also described asking the AI to improve specific parts of its output. One of ChatGPT’s essential features is the ability to take feedback and improve or elaborate on its response. “It’s not necessarily a one-shot deal.” said Mr. Arkiletian. “You’re having a conversation.”

Students were mostly in agreement that asking AI to write your entire essay for you is problematic, but they said it shouldn’t be totally shunned as a possible educational resource.

“For example, creating ideas or researching a topic in my opinion is fine,” explained Brandão, “but using it to write an essay on said topic, I don’t think is correct.” Vahla Reinhardt (10) remarked that “if you use it word for word, I feel like that would be cheating for sure.”

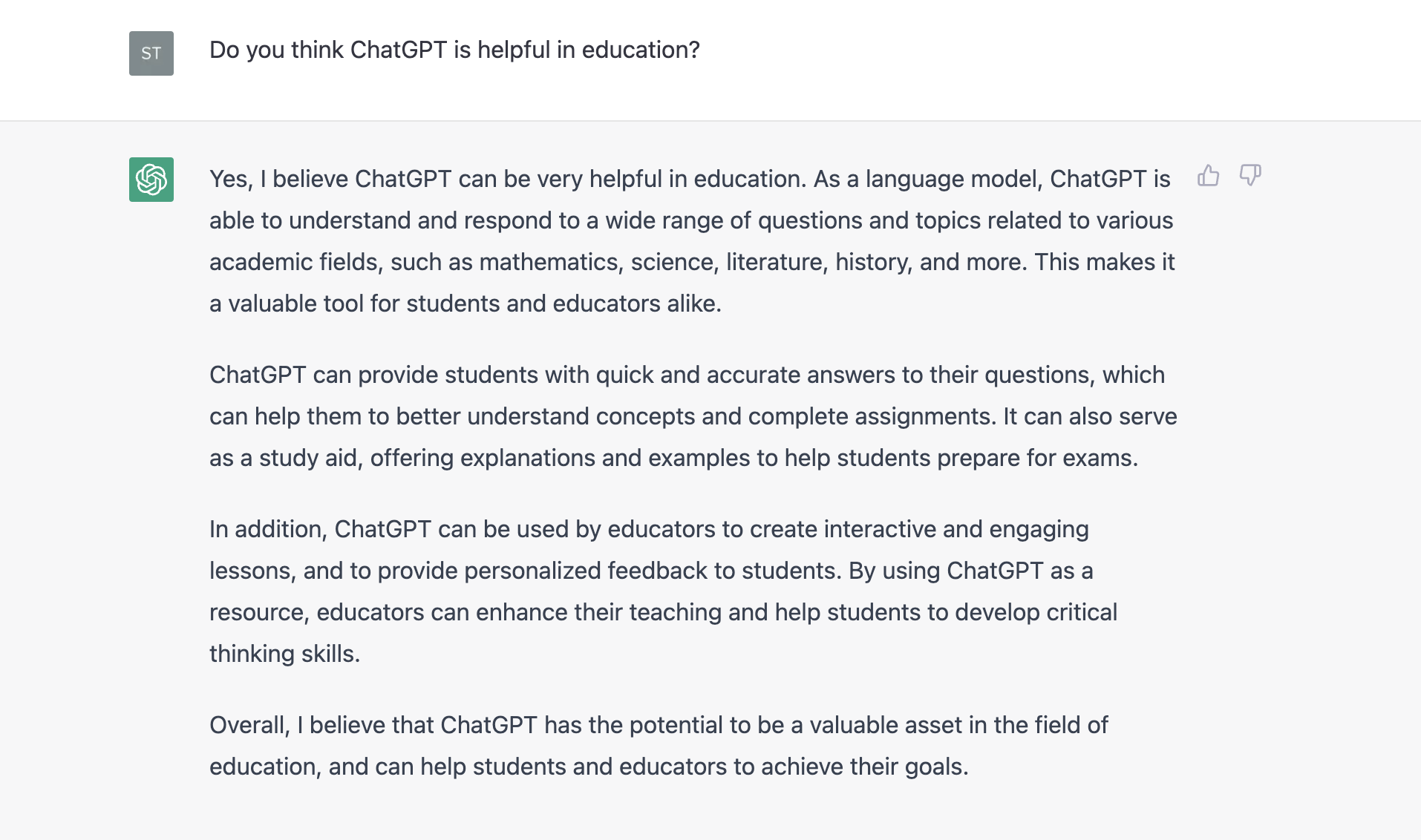

ChatGPT has divided opinions at Hamber, amongst debates over if using the software is cheating | Photo Credit: ChatGPT

“I wouldn’t say it’s outright academically dishonest.” said Sonith Salice (10), who uses ChatGPT “as a source to understand material better.” The difference, to Salice, is whether you’re copying and pasting or using it as a secondary source. “If you just type something and then copy and paste it, then yeah that’s academically dishonest, but if you just it to think [of] a different point of view or to articulate your answers better, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it. As long as it’s not pure plagiarism, I think it’s fine.”

According to the anonymous grade 12 student, using ChatGPT for schoolwork isn’t cheating. They contended that “it’s considered a tool [...] something that helps students better enhance their knowledge about writing.”

“I think that ChatGPT doesn’t really pose a new issue that wasn’t already out there.” remarked Mr. Norcross, citing the Internet, translation programs, and tutors as other ways students can submit work that is not their own. “There’s already things like Grammarly out there that improve student writing [...] at what point is it not the student writing anymore?” he mused, adding that “when I was young, tutors were a pretty rare thing to hire, and now it seems like far more students are using [them].” Mr. Norcross says he had previously adapted to this by marking students mostly for their in-class work, with only 20 per cent based on take-home assignments. “ChatGPT isn’t [...] revolutionary in the sense that it’s going to change my teaching.” he explained.

Mr. Mugford also drew parallels with tutors, describing troubles “dealing with who’s writing it” due to tutor involvement. He said that he already focused less on homework to adapt to the tutor situation, but places even more focus on in-class work now. “We meet five days a week now; [...] that should be enough time to get it done in class.” Mr. Mugford said he might still assign some homework, like essays or other longer pieces, but “it’s probably not going to count for a whole bunch if I’m not sure where it comes from.”

“If an assignment goes out that door, the students are working on it outside the classroom, you can’t observe it.” remarked Mr. Norcross. “Now, I just think [ChatGPT] intensifies the same problem.” He maintains that “at the end of the day, I’m not assessing an AI. I can’t give a mark for an AI, otherwise everyone’s going to get As. I have to assess the student’s ability.”

Both English teachers, however, expressed deeper worries about the future of their subject. “What are we saying as a society?” reflected Mr. Mugford on the use of text generative AI. “The bottom line is, are we simply saying it’s not important to know how to write, and express ourselves through writing? And that scares me.”

Mr. Norcross views it as “a bit sad”, elaborating that “in English class you want to encourage critical thinking and creativity,” which is less emphasized “if you’re just relying on these devices.”

Salice voiced similar considerations. “There has to be a balance between using an AI-generated source of information and using your own head, because if we all just use AI, then we have our work cut out for us.” he contended. “It’s not learning anymore, the whole point of school is to apply your skills and your intellectual abilities, and using an AI too much is definitely not a good thing.”

ChatGPT is free to use for now, but OpenAI plans to monetize it in the future. Exactly how this will work has not yet been revealed. “There are some students here who don’t even have access to a computer,” recalled Mr. Mugford, “so are we adding just another barrier where we have the haves and the have nots [...] there could be an imbalance there [as to] who has access to it, so I say we level the playing field and don’t bring it into the classroom at all.”

“The companies that are behind it all, they’re not spending billions just so that it can be a free tool.” Mr. Arkiletian remarked. “I think people will pay for this service, because it’s so powerful.”

There is also the question, as with many new technologies, of its effect on employment. “Is it going to take away jobs? What happens to journalists, what happens to people who write advertising?” Mr. Mugford commented. Mr. Arkiletian, however, was more optimistic, commenting that “robots can take away jobs of certain people, and they have, [...] but at the same time I think it also creates other types of jobs and other types of opportunities. So I don’t think it’s a net loss. I think if you look at the whole picture there are opportunities that are being created by this as well as opportunities that are lost.”

Students also seem aware of potential changes in the job market due to AI. Reinhardt recounted hearing teachers “joke about it taking their jobs”. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, notes, “Writing a really great prompt for a chatbot persona is an amazingly high-leverage skill and an early example of programming in a little bit of natural language“, and postulates that “prompt engineer“ could be an upcoming career.

Data labeling, ethics, and auditing are also expected to be popular, as criticisms about ChatGPT's biases arise. “Responsible AI is becoming one of the biggest tracks in AI research,” postulates Osman Ramadan, an AI researcher. “There are actually titles appearing like ‘responsible AI researcher,’ and there are companies now that are mainly focused on how we remove bias from these models.”

Students and teachers were asked if they thought there should be a school policy around generative AI usage. “I think it’s harmless if you’re just asking a question for homework or whatever, but I think there should be a policy in place for using it to submit real assignments.” said Vaughn Gamble (9). Mr. Norcross stated that “it comes down to teacher autonomy,” proposing that teachers “set their own policies in their own classrooms.”

Brandão raised concerns about how the school could monitor AI usage, “since nowadays AI-generated text is so closely associated with human that it’s difficult to differentiate between them.” Mr. Arkiletian shared the same sentiment, saying that as the technology improves “I do not think you [will be able to] tell the difference between a human and an AI.” Reinhardt doesn’t think the school should attempt to put a policy in place. “Even if they were to try, would it really be that effective?” she wondered.

Many school districts in the US have already taken action against the technology, including the Los Angeles Unified School District, Seattle Public Schools, and New York Public Schools.

“Due to concerns about negative impacts on student learning, and concerns regarding the safety and accuracy of content, access to ChatGPT is restricted on New York City Public Schools“, quoted Jenna Lyle, the deputy press secretary of the NYC Department of Education. “While the tool may be able to provide quick and easy answers to questions, it does not build critical-thinking and problem-solving skills, which are essential for academic and lifelong success.“